Black Squid has washed up on the cyber-shores of the United States, after first being spotted in Thailand. Unlike its oceanic counterparts, this cyber squid is destructive.

Black Squid has washed up on the cyber-shores of the United States, after first being spotted in Thailand. Unlike its oceanic counterparts, this cyber squid is destructive.

Beincrypto describes the threat like this:

It uses tactics such as anti-virtualization, anti-debugging, and anti-sandboxing before installing itself onto a system. These three processes help nullify any steps that would alarm the users of the malware’s presence.

This is when the squid becomes a worm. Black Squid’s ability to worm its way into other programs gives it immense processing power to scour and mine for cryptocurrencies.

Cryptojacking wreaked havoc on systems across the globe in 2017 and the first half of 2018, then seemed to level off as security measures caught up to miners. However, in the continuing cat-and-mouse game of cybersecurity, cryptojacking is making a quick comeback in 2019.

Black Squid is not alone

Coindesk reports that 50,000 servers worldwide have recently been infected with a new malware that mines for cryptocurrency. The most vulnerable systems are in healthcare, tech, and manufacturing where large servers make for tempting targets.

“As long as it is profitable, cryptojacking will continue to wreak havoc,” predicts Zhiyun Qian, an expert on cryptocurrency and security and associate professor of computer science and engineering at the University of California, Riverside.

Qian adds that the price of Bitcoin has been rising again the past few months. In response, hackers have been willing to come up with different ways to hijack a system.

Black Squid and other types of malware appearing this year are especially troubling to security experts because they are employing new methods to skirt safeguards. Experts say that Black Squid is entering via vulnerable web pages, compromised servers, and infected USB drives and taking a much more muscular approach than its predecessors. Programs like Monero, CoinLoot, and CoinHive (which was shut down last year) have been used by hackers to mine for Bitcoin. In the case of Black Squid, Monero is its preferred mining mechanism.

In many previous cases hijacked systems didn’t show many “symptoms” of being attacked, other than perhaps running slowly. Miners have piggybacked on the large systems of universities or municipalities during off-peak hours and sometimes the only indication is a huge utility bill. Meanwhile, miners are laughing all the way to the bank.

What is it specifically about Black Squid that has experts concerned?

“Unlike the web-based cryptomining attacks, where victim machines are “temporarily” instructed to perform cryptomining (often as long as the browser is open), Black Squid is much more “persistent” and harder to get rid of,” Qian describes. He explains that Black Squid first compromises a victim’s machine to gain a persistent foothold. Then, it embeds a potent combination of exploitation strategies, including the leaked NSA weapon (EnternalBlue) that was leveraged in the infamous WannaCry attack.

MSPs must be proactive

MSPs need to stay on top of outdated vulnerabilities and on top of patching. Delayed patching can leave a major hole in a system.

“As long as all machines are patched and running up-to-date software, it is unlikely to be infected,” states Qian, noting that public facing machines are especially important to safeguard.

“Make sure to update the software preemptively. If any machine is suspected to be compromised already, chances are other machines in the same network are also compromised, as Black Squid would self-propagate,” advises Qian says.

Unlike previous generations of crypto attacks, Black Squid can do more than mine for Bitcoin.

“The machines will effectively be under complete control of the attacker,” describes Qian.

This opens the door to all kinds of other breaches or future payloads being delivered. Black Squid has many tentacles that can reach beyond just mining, something that has Qian and others concerned.

“In addition to the machines’ resources being diverted to cryptomining, anything can really happen in the future,” predicts Qian. That includes ransom being asked, and machines turned into bots that result in denial of service.

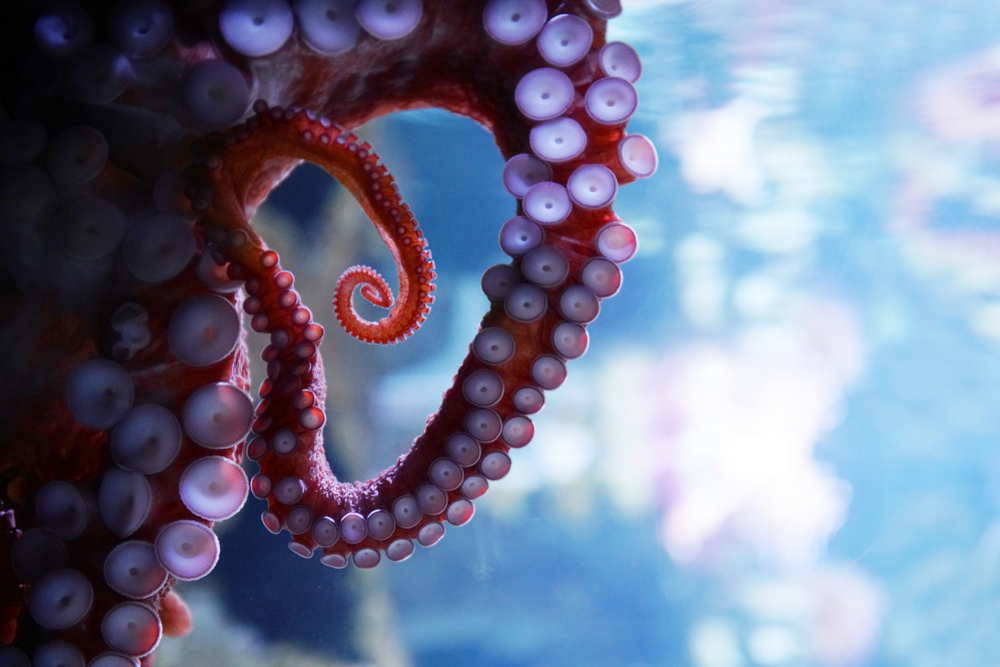

Photo: ND700 / Shutterstock.